Star of David: The Shocking History of the Preeminent Symbol of Judaism

"So if the Star of David isn’t uniquely Jewish, how, when, and why did it end up as the best-known visual symbolic representation of Judaism today?"

Since I’ve been sick most of this week, I figured I’d pass the torch and publish a guest essay by the great Jason Spitalnick, who breaks down the traditions of Judaism and Jewish people with a long-horizon historical perspective on his Recognizably Jewish podcast and blog on Substack.

Some symbols are uniquely Jewish. The menorah is the classic example. The Torah says that god revealed the design for the menorah to Moses, and the menorah has been a uniquely Jewish icon from biblical times to the present.

That’s not true for the subject of Episode 4 of Recognizably Jewish (which you should all listen to if you don’t want to read the whole!) — the Star of David, or Magen David as it’s called in Hebrew.

Magen is the word for shield. And David refers to the biblical figure King David. Unlike the menorah, the Magen David is not mentioned in the Torah, in other parts of the Hebrew bible, or in the Talmud. What’s more, the Star of David, unlike a menorah, is a simple geometric construction. As every Jewish toddler can tell you, it’s formed by overlaying two equilateral triangles—one pointing up and the other pointing down.

In geometry terms, the resulting six-pointed shape is called a hexagram. And because it’s such a simple geometric figure, the hexagram has been used as a design motif by religions and cultures all over the world for thousands of years.

So if the Star of David isn’t uniquely Jewish, how, when, and why did it end up as the best-known visual symbolic representation of Judaism today?

Antiquity & BCE

The Magen David is almost entirely absent from descriptions of, or surviving examples of, Jewish decoration and iconography in antiquity. It is not mentioned as a feature of the first temple built by King Solomon around the 10th century BCE or the second temple built in the sixth century BCE. It does not appear on any surviving coins from areas with known Jewish populations. And with only a few exceptions, it is completely absent from the ruins of ancient synagogues in Israel and elsewhere.

Even the exceptions—that is, ancient Jewish places where a hexagram does appear—indicate that the symbol was not specifically or uniquely Jewish. Perhaps the most famous example is an excavation of a synagogue built in the 4th century CE in Capernaum in the Galilee. The ruins include the remains of friezes featuring hexagrams alongside other geometric symbols, including five-pointed pentagrams, rosettes, and swastikas. That’s right, swastikas. Obviously the swastika–another simple geometric shape that has been used by many cultures–bore no antisemitic connotation in the 4th century. Similarly, it is likely that the hexagram had no particularly Jewish connotation at that time.

Eventually, the hexagram did take on meaning beyond the merely geometric or ornamental. According to the late German-Israeli philosopher and historian Gershom Scholem, the hexagram appeared as a symbol in Jewish mystical traditions as early as the sixth century CE. Used as a magical talisman or amulet, it became known as the Seal of Solomon in recognition of a legendary ring that supposedly allowed King Solomon to interact with the spiritual realm. Even in that context, it was not uniquely Jewish. Indeed, mystical traditions incorporating the hexagram or the Seal of Solomon developed in parallel during early medieval times in Jewish mysticism, Islamic mysticism, and even Western occultism. The name “Seal of Solomon” appears to have originated in Arabic rather than Hebrew. Moreover, mystical traditions–including within Judaism–tended to use the hexagram and the five-pointed pentagram interchangeably as representations of the Seal of Solomon.

While the Seal of Solomon was not uniquely Jewish, its integration into Jewish mysticism did influence aspects of Jewish practice. Scholem wrote about “magical mezuzahs” on which some Jews inscribed signs, symbols, and angelic names to ward off evil spirits. The hexagram was a common sign inscribed on mezuzah scrolls in the Middle Ages.

All of that begs the question: how did the hexagram come to be a Jewish symbol known as the Magen David, the Star of David?

Well, a 13th century German publication called the Book of Desire describes King David’s golden shield. It says it was engraved with what Kabbalah scholars call the 72 Names of God—sequences of Hebrew letters that have the power to overcome the laws of nature. Scholem posits that, sometime in the 13th century, for reasons that are not at all clear, the legend was modified and the engraving of the 72 Names of God on David’s shield was replaced with the engraving of the hexagram—the Seal of Solomon. That’s not a super satisfying explanation, but I haven’t found a more plausible theory.

The first use of the Magen David as an unambiguous visual representation of Judaism happened in 14th century Prague. In 1354, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia Charles IV authorized the Jewish community of the Czech lands to bear a flag of their own. We do not know whether the Jewish people selected the Star of David as an emblem for that flag, or whether the emblem was imposed on them by the authorities. And in either event, we don’t know the reasoning behind the selection. But the resulting red flag emblazoned with a gold Magen David is the first time the symbol was clearly used to represent a Jewish community.

That symbolic use spread within the Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire. In 1512 it appeared on the title page of the first Hebrew book printed in Prague. In 1622, when the Emperor granted noble status to Jacob Bassevi—the first Jew in the empire to be ennobled—Bassevi’s coat of arms included three six-pointed stars. Around the same time, the emblem began appearing on headstones in Jewish cemeteries and was incorporated as a decorative element in Jewish art and architecture.

After Emancipation

The symbolic use of the Magen David throughout Europe really took off in the 19th century—after the so-called emancipation process had played out in various countries.

Scholem — an Israeli historian— suggests it happened because the newly emancipated Jews were looking for a simple symbol of Jewishness, much like the Christian cross. But Scholem points out that, unlike the cross, the Star of David had no historical religious or other doctrinal significance.

He referred to its use at the time as a “meaningless symbol of Judaism.” Notwithstanding that, or perhaps because of it, by the late 19th century, the Magen David was used pretty universally across Ashkenazi Europe. Everyone recognized it as a symbol of Judaism and Jewish community.

Early Zionism

In August 1897, Theodor Hertzl and the Zionist Organization convened the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. The year before the conference, Herzl had proposed that Zionists adopt a white flag with seven Jewish Stars representing the seven hours of the working day—a proposal he believed would reflect the modern, enlightened socialist character of the Zionist movement. But Herzl’s flag idea never gained traction.

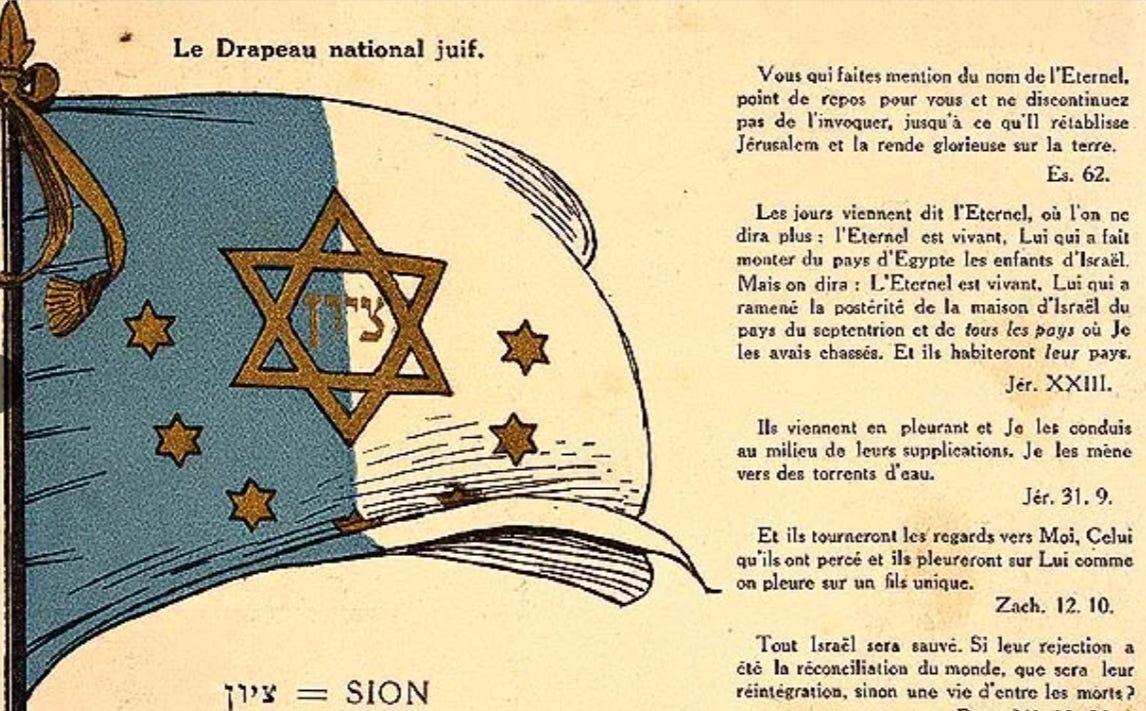

David Wolffsohn, a Lithuanian businessman who later became president of the World Zionist Congress, is credited by many with bringing to the Zionist movement the flag featuring two blue stripes and a blue Magen David.

Wolffsohn wrote that, as he thought about what flag to fly in the hall in Basel, he came to the realization that Jews already had a flag of sorts—namely, the blue and white tallit, or prayer shawl. So he ordered a flag based on the appearance and colors of a tallit, but with a Star of David in the middle. And that flag flew in the Congress Hall in Basel in 1897.

While that story has been confirmed, it should be noted that Jews elsewhere had used a very similar design, featuring a prominent blue Jewish star, prior to 1897. For example, in July 1891, the B’nai Zion Educational Society in Boston flew a white flag with blue stripes, a blue Star of David, and the word Maccabee in blue.

The Holocaust and Discontents

In the early 20th century, the Magen David continued to be widely used to express Jewish affiliation and represent Jewish community. In 1909, a Jewish soccer team in Vienna began competing with a Star of David crest on their uniforms. Famous Jewish boxers like Benny Leonard and Max Baer fought with Jewish Stars on their trunks.

But then, everything changed. Adolf Hitler became the Fuhrer of Germany in August 1934. In May 1938, Nazi propaganda minister Josef Goebbels suggested Jews in the German Reich be forced to wear a "general distinguishing mark" on their clothing. Nothing came of his proposal at the time.

But after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Governor General of Nazi-occupied Poland decreed that all Jewish people over the age of 12 were required to wear 4 inch wide white armbands emblazoned with a blue Star of David. Something similar happened in the summer of 1941 following the German invasion of the USSR.

On September 1, 1941, the chief of the Reich Security Main Office decreed that all Jews in the Reich six years of age or older were to wear a badge consisting of a yellow Star of David against a black background, with the word "Jew" inscribed inside the star in German or in the local language.

If Scholem was right that the Magen David was a “meaningless symbol of Judaism” in the 19th century, there can be no doubt that, after the Holocaust, that was no longer true. By the end of World Wart II, the Star of David had become an undeniable mark of Judaism.

Modern Israel

In the wake of the Holocaust, with Jewish refugees languishing in displaced persons camps throughout Europe, Israel was on the verge of declaring its independence. We discussed much of that history in our episode about David Ben-Gurion. I mention it again because it raises the question of how the Zionist flag featuring the Magen David became the official national flag of sovereign Israel.

As the reality of Israeli independence approached, some Israeli leaders wished to abandon the traditional Zionist flag and the blue Magen David. Moshe Sharett, who would go on to become the second prime minister of Israel, argued that the flag for the new nation must be distinct from the Zionist flag, lest it expose Diaspora Jews to accusations of dual loyalty. You see, by that point, it was fairly common for Jews abroad–especially in America–to fly the Zionist flag as a visible symbol of Jewish community and, of course, Zionism. Sharett and others were worried that, if the Zionist flag became a national flag, Jews across the world might be suspected of dividing their national loyalties between their home countries and Israel.

In the end, however, Sharett’s view did not prevail. David Ben-Gurion proclaimed Israel independent on May 14, 1948. The following month, Israel’s Provisional Government published an announcement in newspapers inviting citizens of Israel to submit proposals for a national flag. The announcement stated that the colors of the flag would be light blue and white, and in the middle there would be a Star of David or seven stars. More than 160 different designs were submitted in response to the newspaper announcement, and the government’s Emblem and Flag Committee selected one featuring both a Magen David and seven gold stars. However, in a surprise turn of events, the Provisional Council of State–the Israeli legislature before the Knesset–rejected the government’s proposal. It then appointed a committee of its own, and, after consulting representatives of Jewish communities in the Diaspora, decided on July 28, 1948 to adopt the Zionist flag as the Israeli state flag. That decision was approved by the full Provisional Council on October 28, 1948–making the Zionist flag with its blue Magen David the official flag of Israel.

Conclusion

The Magen David has remained symbolically important since the founding of Israel. Natan Sharansky wrote about Jewish refuseniks in the Soviet Union secretly passing along Star of David pendants as symbols of solidarity. Today Jews and their allies globally proudly wear the Magen David as a necklace or on other jewelry.

Indeed, the symbol has sometimes taken on a life of its own in the American cultural zeitgeist. In the 1990s, the global pop icon Madonna became interested in Kabbalah and began wearing and using certain Jewish iconography, including the Magen David. In 2022, Kanye West was suspended from Twitter for posting an image of a swastika inside a Star of David. I suspect he wasn’t thinking about the 4th century synagogue in Capernaum.

Listen to his episodes here:

This piece of journalism was edited and brought to you by Toni Airaksinen, Senior Editor of Liberty Affair and a journalist based in Delray Beach, Florida. Follow her on Substack, on X @Toni_Airaksinen and on Instagram.

If you enjoyed this essay, please follow . Nothing but good things to say about his writing, and I hope to feature more from him, if the readers would like. Comment below and let us know!

Oddly though the harbinger of the arrival of the Jewish messiah was a star…